ARFID: The eating disorder even doctors don't know about

An insight into living with the fear of foods

Meet Emma

Imagine having Weetabix for breakfast, a cheese spread sandwich for lunch, and half a plate of chips for dinner. Now imagine having those dishes 365 days a year. Chloe Peck speaks to Bradford-born Emma Naylor, a girl suffering with the eating condition even doctors don't know about.

For 18-year-old Emma, those dishes you’re imagining are a bland reality she faces day in day out as a sufferer of Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID).

Emma is the epitome of a fussy eater. But it's much deeper than that; it’s a psychological condition which prevents her from being able to try new foods. The fear of experimenting with foods is so deeply instilled in Emma that she physically cannot get a morsel of a new food past her lips.

The condition results in an incredibly restricted diet, with sufferers meticulously selecting which foods make the cut as ‘safe’, and which do not, though at a dangerous price.

In Emma’s case, her food palate has been whittled down to just 11 foods. She says: “I eat Hovis white bread, Dairylea cheese spread, Petit Filous peach-flavoured yogurts, Mini Cheddars, Fries to Go, Freddo bars, sliced Pink Lady apples, grapes, bananas, Weetabix and pears.” But the pears must be soft, she assured me.

“She lives on less than my friends’ toddlers,” her mother says.

The flashing blue lights of ambulances rushing her to hospital have almost become routine to Emma. “They’re saying there is a strain on my heart because of my eating. I keep going blue and not being able to breathe.

“I’ve been in hospital about once a week for the past three months. I get put on a drip filled with the vitamins that I’m missing and given an oxygen mask to stabilise my breathing. I go to the doctors biweekly to have blood tests. They check my iron, my electrolytes, my white blood cells and my blood clotting.”

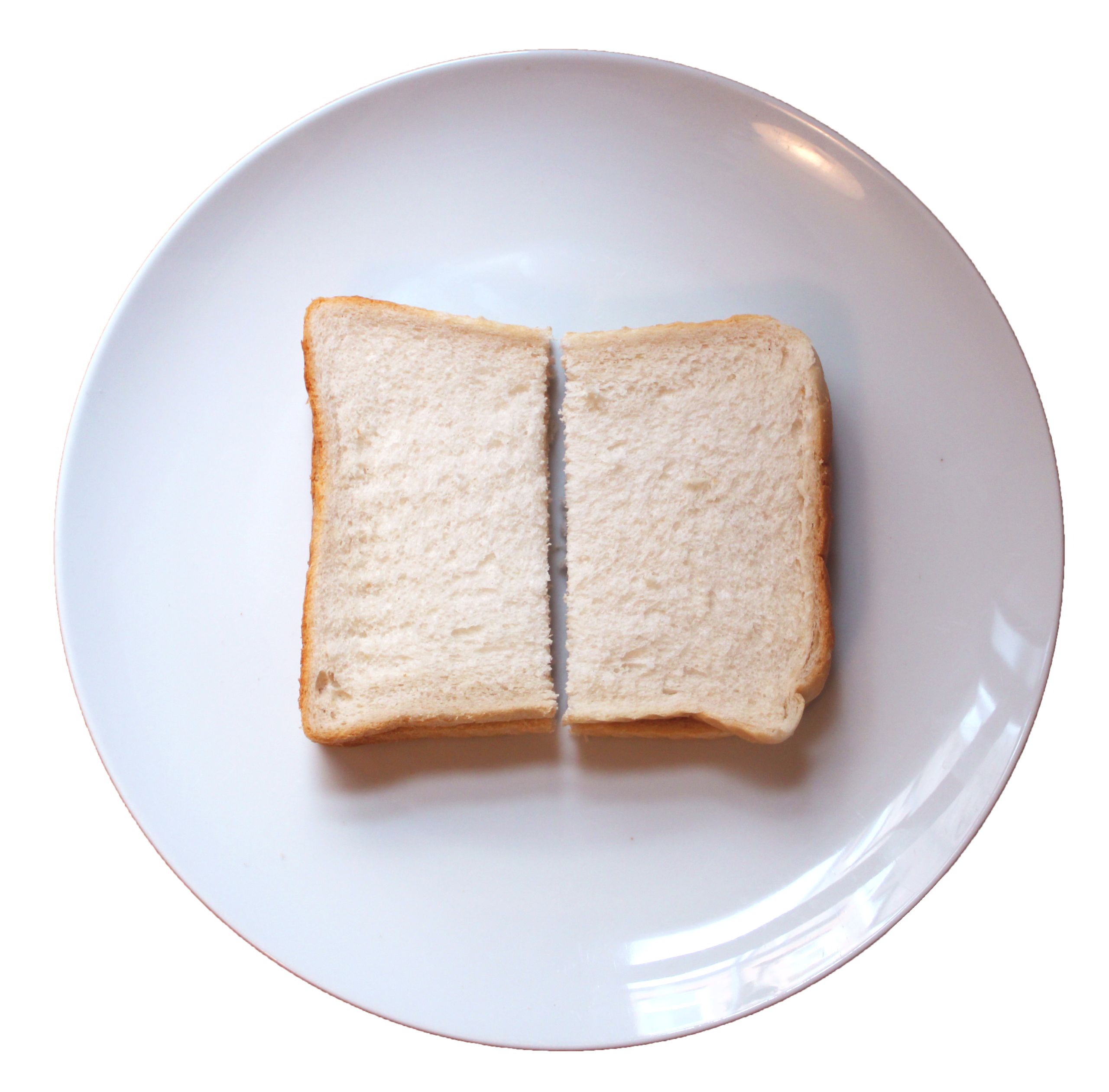

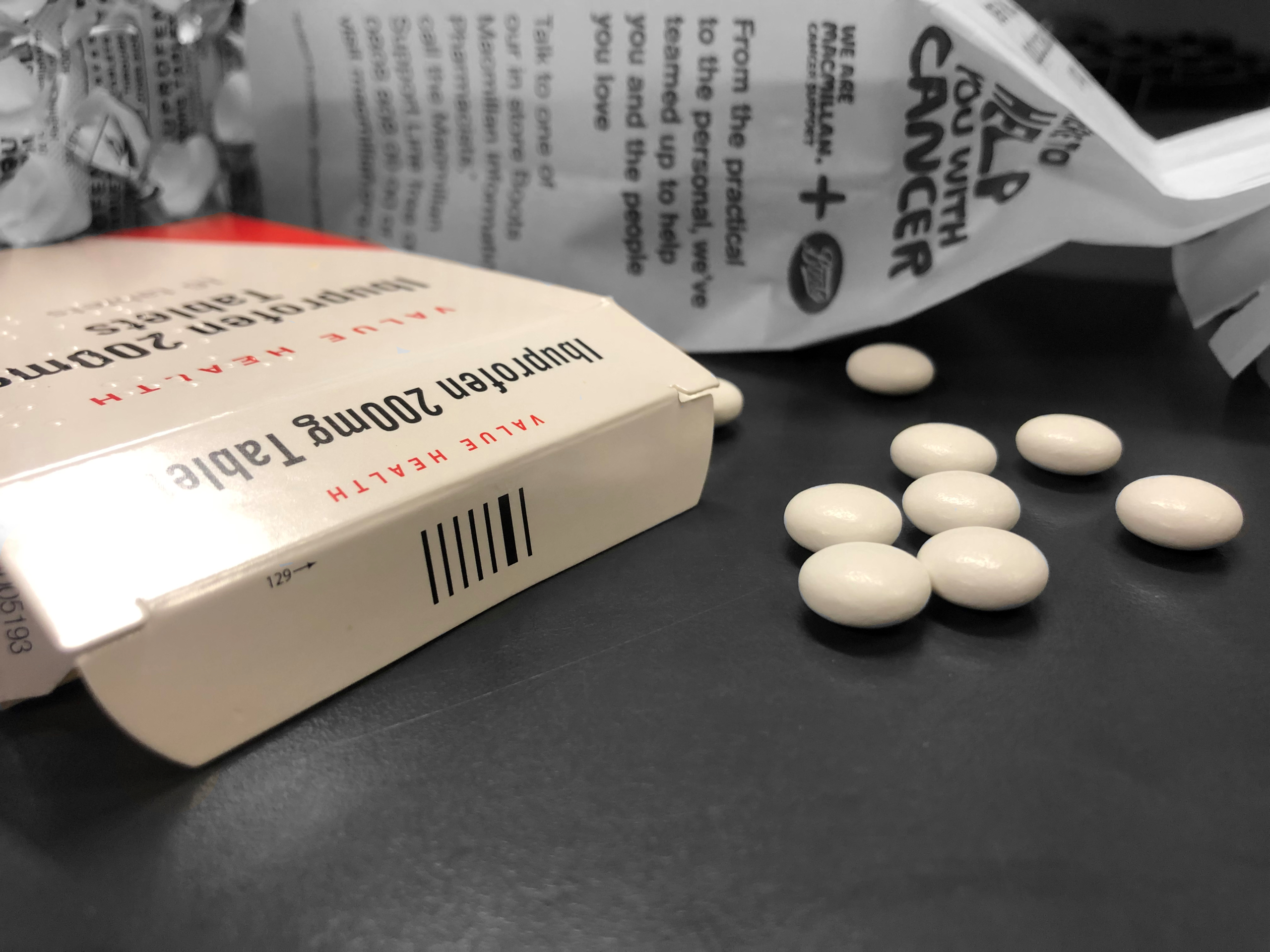

Emma gulps down 24 tablets a day. Eight of these tablets are the same drug, taken in an effort to replenish the vital nutrients that she is missing.

She tells me that she has been diagnosed with autism, which is common in individuals with ARFID. As she twiddles her thumbs and entwines her fingers in her hair, the apprehension on opening up about her eating condition is palpable.

Emma's fear of trying new foods stems from being sick, “I don’t like being sick. It’s my biggest fear.”

I look around Emma’s bedroom and see shelves, lined from end to end with medals and trophies from a lifelong hobby sacrificed because of the effects of her poor diet.

“I had to stop dancing because I became too unwell to do it. Simple things like that can break my bones.

When I ask of her hobby now she says: “Sleeping.”

Emma seems withdrawn and on edge, hesitant to drop her façade.

"Her blood test results came back worse than somebody undergoing chemotherapy."

Andrea Naylor

The newly recognised eating condition is a feeding disturbance based on a fear of trying new foods, resulting in significant nutritional deficiency. Unlike other eating disorders, ARFID does not involve any distress about weight gain or body image.

For most people with ARFID the fear of trying new foods stems from an aversive experience such as being sick or choking, however the sensory features of foods such as texture, flavour and smell can also prevent individuals from trying something new.

Emma’s autism increases her hypersensitivity to these features.

ARFID accounts for between 5 and 22% of all eating disorders among adolescents.

(Fitzgerald and Frankum, 2017)

Clarissa Martin

Head of Child Health Services &

Lead of Specialist Feeding Disorder Services at Midlands Psychology

What is the psychology behind those with ARFID avoiding foods?

Consultant clinical psychologist, Ms Martin, says: “ARFID is caused by a complicated combination of neurological, medical, social and emotional factors. Any relative painful experience with food is going to create a negative association to avoid it. It’s a fear-based conditioned behaviour.

“Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can adapt somebody’s perspective on food. They need to be re-educated and their palate expanded. The understanding of flavours takes place in the first stage of development between four and seven months when the brain is open to any flavour, and if you miss that window of opportunity to experience them, you would be very reluctant to eat anything different.”

Clarissa’s concept suggests that babies that struggled to wean onto solid foods may have missed their window of opportunity, and subsequently have a very restricted palate.

Will ARFID resolve on it's own?

Ms Martin, says, “ARFID requires clinical input. It’s not going away naturally. This kind of advice about starving the child to get the child to eat is not working. If not provided with food they like, children with ARFID will die from malnutrition or starvation."

What treatment is available?

She explains that there are different pathways of treatment around the country. Traditionally the management of individuals with feeding problems has been dietetic support, with additional therapy and paediatrician input. But because ARFID is a mental health condition, individual’s require psychological treatment.

She says: “Not many professionals specialise in feeding problems in the UK, we are one of few in the country, we are receiving referrals from all around the nation for people with this condition. We take-on children who have been in treatment for ARFID for a couple of years with no progression, from specialist hospitals such as Great Ormond Street.”

Andrea's story

Emma's mother, Andrea Naylor, 52, enlightens me with answers to questions that fall upon deaf ears.

“About three or four years ago it really took a turn for the worse. She started to pass out in the shower and I noticed that she was getting really pale. I had been to the doctors a few times and they just didn’t take it seriously and then she passed out at school.

"They did a blood test and her blood test results came back worse than somebody undergoing chemotherapy."

“They wanted to admit her to hospital and put a nasogastric feeding tube in her nose, but it was two days before Christmas, the hospitals were busy, and she really didn’t want to go. She was getting really upset and agreed at that time that she would drink Complan vanilla milkshake.

“She struggles to get it down, but she tolerates it. It’s basically the complan that’s keeping her out of hospital.”

Although Emma was officially diagnosed with Selective Eating Disorder aged seven, (which was subsequently renamed as ARFID), Andrea argues that the condition needs more support and recognition. She often takes Emma to hospital for appointments and tells the doctor that Emma has ARFID, only to be met with confusion from health professionals who are entirely unaware of the eating condition; a repetitive and tiresome cycle.

She says that Emma wears acrylics on her nails to conceal the fact that her nails have stopped growing, and that her hair is so thin it has started dropping out.

"Emma even takes the contraceptive pill to stop her periods, as she cannot afford to lose the iron each month."

She tells me that Emma’s teeth have begun to crumble because all of the foods she eats are so soft that she doesn’t have to chew, and how at age 18 her daughter, “doesn’t know how to use a knife and fork.”

“It’s really difficult to have a daughter with ARFID because you don’t feel like you’re fulfilling your duties as a mother, because as a mother your instinct is to feed your children and I just can’t do that for Emma. It’s been such a battleground over the years. I’ve tried everything, but she just won’t eat.

“Even her medication has to be altered because she can’t cope with the plastic coating on tablets, so I have to go to various chemists or order it in. Her prescriptions have to be changed to accommodate her otherwise she won’t take that either.

“We went away to America when she was five or six and I thought we would be able to get Emma’s foods there, I wasn’t fully aware of how bad the problem was; when we came home, she had lost 10 pounds within a fortnight and was really poorly. We had to physically carry her off the plane because she was so weak as she just wouldn’t eat the whole time that we were there.”

Emma's continues...

Reeling off a list of health problems she has that were induced by her disordered eating, Emma jokes, “we could be here for a while.”

Emma suffers with osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, anaemia, vitamin D deficiency, low body temperature, low heart rate, low magnesium and low potassium levels. She also mentions that a few days prior to our meeting she was on a drip for potassium, and that she has low neutrophils which means she has a weakened immune system and struggles to fight off infections.

She lists them off casually, signifying how acquainted she is to her ailments.

The eating condition also threatens to limit Emma’s future opportunities; she has chosen to commute to Leeds Trinity University next year, the closest university to home, as she would not be able to face the kitchen in shared student accommodation.

Andrea Naylor on having a child with ARFID.

Andrea Naylor on having a child with ARFID.

Tina Pennock

Dietitian, Specialising in ARFID

Tina Pennock, a qualified dietitian of 22 years, is an expert in paediatrics and specialises in treating ARFID. She says: “I tend to see a lot of people have what we call a ‘beige diet’. They eat a lot of the carbohydrates; breads, biscuits, crisps, cereals and that sort of thing. There’s rarely any fruit or vegetables going in their diet.”

She explains that ARFID is typically a condition that develops from birth, with babies often struggling to wean from breast or bottle feeding to begin eating solid foods. It is around the 18-month mark that parents begin to notice a reduction in the amounts and varieties of foods that their child will eat.

She says that parents find it frustrating when they’re preparing food and their child will not eat it, as they are very concerned in terms of health, growth and development.

This often results in the parents placing the blame on themselves for their children’s eating habits. But it is quite the reverse, Mrs Pennock explains: “It is very much a condition. It’s not just somebody who’s being fussy. It’s not just somebody who’s being controlling. It’s a real condition which people need to recognise.”

Mrs Pennock describes how parents are often reluctant to seek treatment from dietitians, due to previous unsuccessful experiences with health professionals who have lacked understanding of the eating condition, and thus suggested feeding their child greens or letting them go hungry.

She says: “We are completely the opposite, we understand it. I think when parents come to see us they are quite surprised. It’s almost like we give them permission and say it’s okay to give your child chicken nuggets and chips every day if that’s the only food that they will eat. I think they find it reassuring that they’re not going to be judged for feeding their child an unhealthy diet."

Mrs Pennock explains that primarily vitamins and minerals such as zinc, iron, calcium and vitamin B12 are supplemented due to the lack of vegetables and meat products that the patients have in their diets. She says they begin by switching to fortified breads and cereals which contain vitamins and minerals, then a detailed diet history is taken to see what other nutrients need to be added through medication.

Cases of ARFID vary in severity. Both Mrs Pennock and Ms Martin have patients fed purely by a nasogastric feeding tube which all fluids and nutrition go in via, after their lists of safe foods gradually got more and more limited to the point where there was no food going in.

Andrea, Emma's mother, explains that when the wotsits packaging changed stating that the crisps were ‘baked not fried’ Emma refused to eat them, and just like that another food was struck off the list.

“A few years ago, Emma was fed up and we agreed that she would try plain pasta. I cooked a single shell of white pasta and told her if she ate it she could go and watch a show in London that she really wanted to watch. She sat at the table with this piece of pasta, shaking and crying. She must have sat there for an hour and a half and she kept trying to put it to her mouth. I could see that she really wanted to try it, and, in the end, she threw-up all over her plate. She didn’t even get it in her mouth.”

But treatment options for ARFID in the UK are very sparse.

A study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health found that of 657 paediatricians, 63% were unfamiliar with ARFID and of the 36% who suspected a diagnosis of ARFID in a previously assessed patient, 30% misdiagnosed the patients, meaning theoretically only 7% of patients with ARFID were diagnosed correctly.

It is the undeniable lack of recognition surrounding ARFID that commonly leads to the sufferers being diagnosed and treated inappropriately for their condition.

Many people suffering with ARFID trawl through years of unsuitable treatment being passed back and forth from GPs to dietitians to therapists or are passed off as mere ‘fussy eaters.”

Aged seven, Emma was treated with a round of hypnotherapy which was unsuccessful. Since then she has been supplemented with the vitamins she lacks, instead of receiving treatment to change her eating condition. Andrea believes that, like any other medical condition, help should be accessible for those who would like it, and the treatment should be free.

“I should not have to offer to pay someone privately in London £300 for treatment which is the only option we’ve been given. If my child had a broken leg somebody would fix it on the NHS, there should be more support on the NHS to treat ARFID.”

It is evident that there needs to be more support for people like Emma, who are suffering serious health consequences from their diets, but are not receiving appropriate treatment because their cases are not at breaking point.

An insight into living with ARFID

An insight into living with ARFID

As Emma grows older, her mother believes her chances of recovering are next to none, “I don’t think she’ll ever try a new food. I think at 18-years-old she just won’t. She is physically scared of food.”

Emma says, “I just wish people knew that it’s something inbuilt. If this was a choice I wouldn’t want to be this way. I wouldn’t choose to be like this, I wouldn’t wish it on anybody else because it’s not nice.”

In the future maybe ARFID will be recognised for what it is; not just fussy eating, and treatment for sufferers like Emma will become freely available.

If you identify with the symptoms mentioned or think somebody you love has ARFID reach out and seek support.